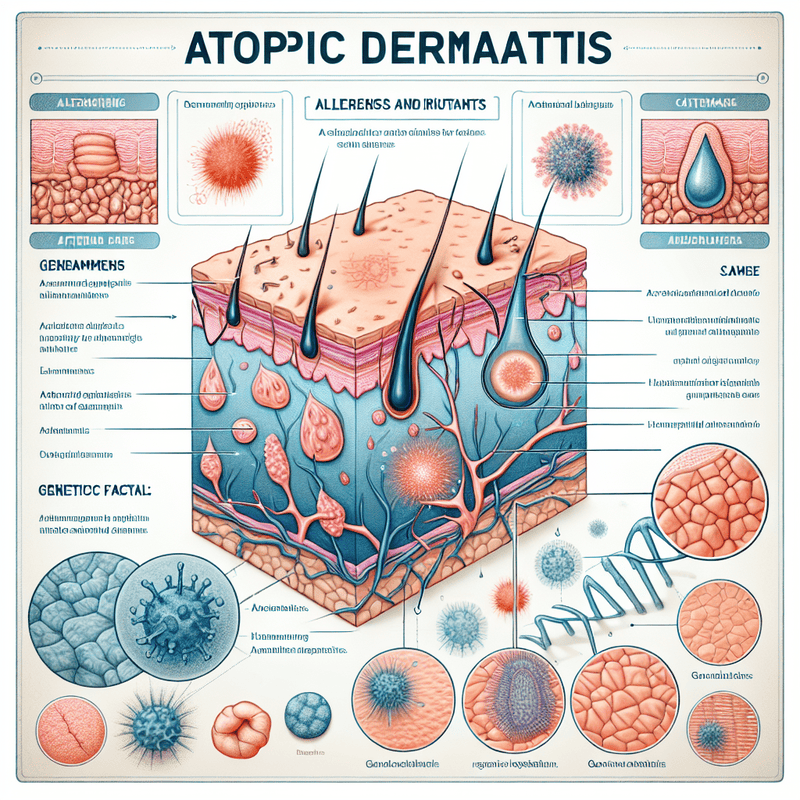

Genetic Factors Contributing To Atopic Dermatitis

Atopic dermatitis, commonly known as eczema, is a chronic inflammatory skin condition characterized by itchy, red, and swollen patches of skin. While environmental factors and lifestyle choices play significant roles in the manifestation and exacerbation of this condition, genetic factors are also crucial in understanding its etiology. The interplay between genetic predisposition and environmental triggers forms the basis of the complex pathophysiology of atopic dermatitis.

One of the primary genetic factors contributing to atopic dermatitis is the mutation in the filaggrin (FLG) gene. Filaggrin is a protein essential for the formation and maintenance of the skin barrier. It helps in the aggregation of keratin fibers in the epidermis, which is vital for the skin’s protective function. Mutations in the FLG gene lead to a compromised skin barrier, making it more susceptible to irritants, allergens, and pathogens. Consequently, individuals with FLG mutations are at a higher risk of developing atopic dermatitis, as their skin is less capable of retaining moisture and more prone to inflammation.

In addition to FLG mutations, other genetic variations also contribute to the susceptibility to atopic dermatitis. Polymorphisms in genes involved in the immune response, such as those encoding for cytokines and their receptors, have been implicated in the disease. For instance, variations in the interleukin-4 (IL-4) and interleukin-13 (IL-13) genes can lead to an exaggerated immune response, promoting inflammation and the characteristic symptoms of atopic dermatitis. These cytokines play a pivotal role in the Th2 immune response, which is often upregulated in individuals with atopic dermatitis, leading to chronic inflammation and skin barrier dysfunction.

Moreover, genetic studies have identified several loci associated with atopic dermatitis through genome-wide association studies (GWAS). These loci include regions on chromosomes 1q21, 11q13, and 17q25, among others. The identification of these loci has provided insights into the complex genetic architecture of atopic dermatitis, highlighting the polygenic nature of the disease. Each of these loci contains multiple genes that may contribute to the pathogenesis of atopic dermatitis through various mechanisms, including skin barrier function, immune regulation, and inflammatory pathways.

Furthermore, epigenetic modifications also play a role in the development and progression of atopic dermatitis. Epigenetic changes, such as DNA methylation and histone modification, can influence gene expression without altering the underlying DNA sequence. Environmental factors, such as exposure to allergens and pollutants, can induce epigenetic changes that affect the expression of genes involved in skin barrier function and immune response. These epigenetic modifications can be heritable, potentially explaining the familial aggregation of atopic dermatitis.

In conclusion, the genetic factors contributing to atopic dermatitis are multifaceted and involve a combination of gene mutations, polymorphisms, and epigenetic modifications. The FLG gene mutation is a well-established genetic factor that compromises the skin barrier, while variations in immune-related genes contribute to the inflammatory response characteristic of atopic dermatitis. Genome-wide association studies have further elucidated the polygenic nature of the disease, identifying multiple loci associated with its susceptibility. Additionally, epigenetic modifications influenced by environmental factors add another layer of complexity to the genetic landscape of atopic dermatitis. Understanding these genetic factors is crucial for developing targeted therapies and personalized treatment strategies for individuals suffering from this chronic skin condition.

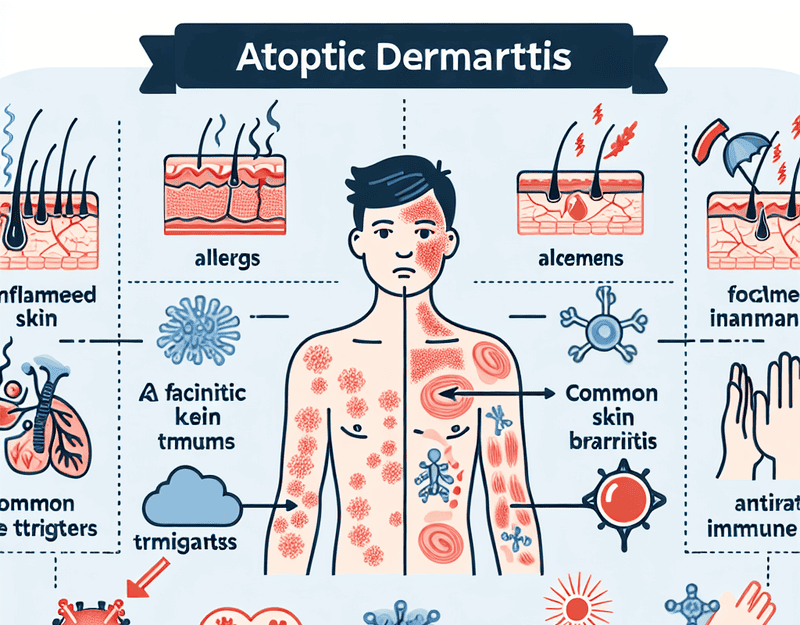

Environmental Triggers Of Atopic Dermatitis

Atopic dermatitis, commonly known as eczema, is a chronic skin condition characterized by inflamed, itchy, and red patches of skin. While the exact cause of atopic dermatitis remains elusive, it is widely accepted that a combination of genetic, immunological, and environmental factors contribute to its development. Among these, environmental triggers play a significant role in exacerbating the symptoms and frequency of flare-ups in individuals with atopic dermatitis.

One of the primary environmental triggers of atopic dermatitis is exposure to allergens. Common allergens such as pollen, dust mites, pet dander, and mold can provoke an immune response in susceptible individuals, leading to inflammation and itching. For instance, dust mites, which thrive in household environments, are a well-documented trigger. These microscopic organisms can be found in bedding, upholstered furniture, and carpets, making it challenging to avoid them completely. Similarly, pet dander, consisting of tiny flakes of skin shed by animals, can also induce flare-ups, particularly in those who are already sensitized to these allergens.

In addition to allergens, irritants are another significant environmental factor that can aggravate atopic dermatitis. Everyday substances such as soaps, detergents, and fragrances can strip the skin of its natural oils, leading to dryness and irritation. This is particularly problematic for individuals with atopic dermatitis, as their skin barrier is already compromised. Consequently, exposure to these irritants can result in increased skin sensitivity and a higher likelihood of flare-ups. Moreover, certain fabrics, such as wool and synthetic materials, can also irritate the skin, further exacerbating the condition.

Weather conditions and climate changes are also influential environmental triggers. Extremes in temperature and humidity can have a profound impact on the skin. For example, cold, dry air during winter months can lead to decreased skin hydration, making the skin more prone to cracking and itching. Conversely, hot and humid conditions can cause excessive sweating, which can irritate the skin and lead to flare-ups. Additionally, sudden changes in weather can disrupt the skin’s natural balance, making it more susceptible to irritation and inflammation.

Pollution is another environmental factor that has been linked to atopic dermatitis. Airborne pollutants such as cigarette smoke, vehicle emissions, and industrial chemicals can exacerbate the condition. These pollutants can penetrate the skin barrier, leading to oxidative stress and inflammation. Studies have shown that individuals living in urban areas with high levels of pollution are more likely to experience severe symptoms of atopic dermatitis compared to those in less polluted environments.

Furthermore, stress, although not a direct environmental factor, can influence the severity of atopic dermatitis. Stress can weaken the immune system and disrupt the skin barrier function, making the skin more vulnerable to environmental triggers. This creates a vicious cycle where stress exacerbates the condition, leading to increased stress and further aggravation of symptoms.

In conclusion, environmental triggers play a crucial role in the manifestation and exacerbation of atopic dermatitis. Allergens, irritants, weather conditions, pollution, and stress are all significant factors that can influence the severity and frequency of flare-ups. Understanding these triggers and taking proactive measures to minimize exposure can help individuals manage their condition more effectively. By maintaining a clean living environment, using gentle skincare products, and adopting stress-reduction techniques, those affected by atopic dermatitis can better control their symptoms and improve their quality of life.

Immune System Dysregulation In Atopic Dermatitis

Atopic dermatitis, commonly known as eczema, is a chronic inflammatory skin condition characterized by itchy, red, and swollen patches of skin. One of the primary underlying factors contributing to the development and persistence of atopic dermatitis is immune system dysregulation. This dysregulation involves a complex interplay of genetic, environmental, and immunological factors that disrupt the normal functioning of the immune system, leading to the characteristic symptoms of the disease.

To begin with, genetic predisposition plays a significant role in the immune system dysregulation observed in atopic dermatitis. Individuals with a family history of atopic diseases, such as asthma, allergic rhinitis, and eczema, are more likely to develop atopic dermatitis. This genetic susceptibility is often linked to mutations in genes responsible for skin barrier function and immune regulation. For instance, mutations in the filaggrin gene, which is crucial for maintaining the integrity of the skin barrier, can lead to increased skin permeability and heightened immune responses to environmental allergens.

Moreover, environmental factors further exacerbate immune system dysregulation in atopic dermatitis. Exposure to allergens such as pollen, dust mites, and pet dander can trigger immune responses in genetically predisposed individuals. Additionally, irritants like harsh soaps, detergents, and pollutants can damage the skin barrier, making it easier for allergens to penetrate and activate the immune system. This environmental exposure leads to a vicious cycle of skin barrier disruption and immune activation, perpetuating the inflammatory process.

In the context of immune system dysregulation, the role of T-helper cells, particularly Th2 cells, is of paramount importance. In individuals with atopic dermatitis, there is an imbalance between Th1 and Th2 cells, with a predominance of Th2-mediated immune responses. Th2 cells produce cytokines such as interleukin-4 (IL-4), interleukin-5 (IL-5), and interleukin-13 (IL-13), which promote the production of immunoglobulin E (IgE) and the recruitment of eosinophils. These cytokines contribute to the inflammatory response and the characteristic symptoms of atopic dermatitis, including itching and redness.

Furthermore, regulatory T cells (Tregs), which normally function to suppress excessive immune responses and maintain immune homeostasis, are often dysfunctional in individuals with atopic dermatitis. This dysfunction results in a failure to adequately control the Th2-mediated inflammatory response, leading to chronic inflammation and skin lesions. The impaired function of Tregs is thought to be influenced by both genetic factors and environmental triggers, further highlighting the multifactorial nature of immune system dysregulation in atopic dermatitis.

Additionally, recent research has shed light on the role of the skin microbiome in immune system dysregulation in atopic dermatitis. The skin of individuals with atopic dermatitis often exhibits an altered microbial composition, with a predominance of Staphylococcus aureus. This bacterial imbalance can exacerbate inflammation by producing toxins that further damage the skin barrier and stimulate immune responses. The interaction between the skin microbiome and the immune system is an area of active investigation, with the potential to uncover novel therapeutic targets for managing atopic dermatitis.

In conclusion, immune system dysregulation in atopic dermatitis is a multifaceted process involving genetic predisposition, environmental factors, and complex immunological mechanisms. The interplay between these factors leads to an imbalance in immune responses, resulting in the chronic inflammation and skin barrier dysfunction characteristic of the disease. Understanding the underlying causes of immune system dysregulation in atopic dermatitis is crucial for developing effective treatments and improving the quality of life for individuals affected by this condition.