As i mentioned on Monday, a fabulously perceptive and captivating exhibition titled Verschwindende Vermächtnisse: Die Welt als Wald / Disappearing Legacies: The World as a Forest opened at the Zoological Museum in Hamburg back in November. The show follows on the footsteps of Alfred Russel Wallace, a British naturalist who, over 150 years ago, (co-)formulated the principle of species evolution during research trips to South America and Southeast Asia. 150 years is not a very long time. Yet, if Wallace were to return to these tropical habitats, chances are that he would not recognized them. The rainforests have been destroyed at a very rapid pace by heavy logging, agricultural clearance and urbanisation. Large numbers of species have been driven to extinction in the process. Would Wallace still be able to develop the theory of evolution through natural selection in this context?

Exhibition view (entry lithograph of Amazonia.) Photo: ReassemblingNature.org, Michael Pfisterer

Armin Linke, Orangutan in the Tanjung Puting National Park, Kumai, Kalimantan Tengah (Borneo) Indonesia, 2017. Photo: © Armin Linke

Disappearing Legacies: The World as a Forest gathers contemporary artworks as well as zoological and botanical objects to investigate the changes in the tropical regions that Wallace once traveled and to shed light on the ecological issues faced by today’s fauna and flora of Amazon, Indonesia, Malaysia and Singapore.

The show also interrogates our traditional concept of nature: how can it be mediated and maintained in a context characterized by extinction, deforestation and climate change?

The artworks are exhibited inside the main exhibition space of the museum and not in a dedicated, white space gallery. The curatorial decision means that families who enter the space to see taxidermied bears and exotic flowers are confronted with challenging questions and artifacts they might not otherwise get a chance to explore in such details. It might look like an unusual curating choice to some but i thought it was a brilliant move as 1. I’m always in favour of broadening the audience of contemporary artworks 2. by installing the works in the middle of a traditional Museum of Natural History, the curators invite us to reflect on the role that such an institution should play in the age of the anthropocene and Sixth Mass Extinction. Is our knowledge about biology and evolution in need of an update?

Here’s a quick and very partial tour of the exhibition:

Shannon Lee Castleman, Tree Wounds, Muna Island, Southeast Sulawesi, 2010-2011

Shannon Lee Castleman, Tree Wounds, Muna Island, Southeast Sulawesi, 2010-2011

Shannon Lee Castleman, Tree Wounds, Muna Island, Southeast Sulawesi, 2010-2011. Verschwindende Vermächtnisse: Die Welt als Wald. Photo: UHH/CeNak, Reiss

I was very moved by the Tree Wound photographs that Shannon Lee Castleman took during a field trip to Muna Island in Indonesia.

While visiting the island, the artist noticed enormous wounds on many of the older teak trees in the conservation forest. These forests are older teak plantations that have been awarded “conservation” forest status—not because of bio-diversity (which was devastated by timber planting in the 19th and 20th centuries) but because former plantations maintain the water table for the island. Castleman was told that since felling teak in these forests is illegal, impoverished villagers who pass by large teak trees will give a tree one cut with an axe after another … until finally the tree falls or dies and no-one is to blame.

The portraits of these wounded trees recount, on a micro-scale, the tragedy of deforestation and illegal logging taking place all over the world.

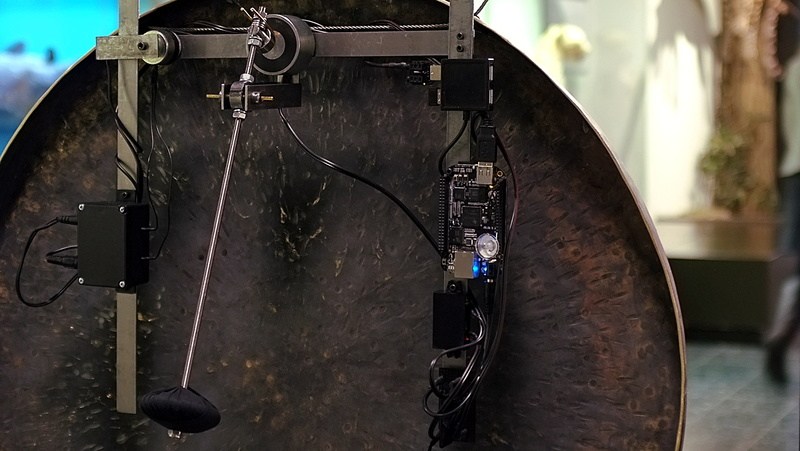

Julian Oliver & Crystelle Vũ, Extinction Gong, 2017

Julian Oliver & Crystelle Vũ, Extinction Gong (details at the back of the gong), 2017

The Extinction Gong, by Julian Oliver and Crystelle Vũ, is a ceremonial automaton for the Sixth Mass Extinction.

The Chinese ‘Chao Gong’ beats to the rhythm of species extinction, estimated by biologist E.O. Wilson to be about 27,000 losses every year, or once every 19 minutes. Even though this is a conservative estimate, it is still much higher than the average background rate (the non-anthropogenically influenced extinction rates) of plant, animal and insect species extinction.

Should biologists declare a new species extinct while the Extinction Gong is active it will receive an update via a 3g link and perform a special ceremony: four strikes in quick succession alongside a text-to-speech utterance of the Latin Name of the species lost, resonating through the gong.

The front side of the Chinese ‘Chao Gong’ is painted with the Extinction Symbol, the official mark of the Sixth Mass Extinction. The back, however, reveals the engineering of the artwork.

“This diametric expresses a brutal and contradicting irony – while advances in science and technology augment the devastating impact of human endeavours over wild habitats, so are they our best means of studying and understanding it.”

I found the work extremely moving. It gives presence and dignity to insects, plants and animals who disappear quietly while most of us remain deaf and indifferent to the loss of biodiversity.

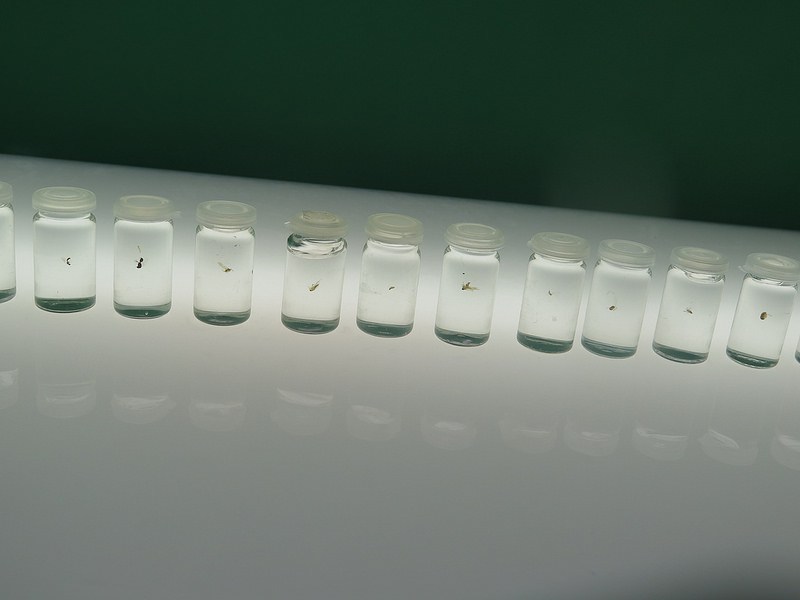

Robert Zhao Renhui / The Institute of Critical Zoologists, Useful Nature, Useless Nature, 2017

Robert Zhao Renhui / The Institute of Critical Zoologists, Useful Nature, Useless Nature, 2017

Robert Zhao Renhui / The Institute of Critical Zoologists, Useful Nature, Useless Nature, 2017

Over the past few years, Robert Zhao Renhui has been documenting the ways in which the human species is altering other life forms. Directly or indirectly. His photographic works show animals, insects and plants that had to evolve in order to cope with the pressures of a fast changing world or as the direct result of human intervention and for purposes ranging from scientific research to the desire for ornamentation.

For the exhibition in Hamburg, the artist focused his research on insects. Over a single day, Zhao gathered insect carcasses from windows, insect traps, house corners and other crevices in his studio in Singapore. The carcasses reveal the wide variety of insect life that co-exists with human beings yet go largely unnoticed.

The carcasses are neatly aligned in one exhibition window. A nearby display features a collection of gadgets and chemicals used to repel and kill insects.

One of the questions raised by Zhao regards our selective love for nature and for insects in particular: why do we classify some species as useful resources or products while we regard others as pests or vermin? What gives us the right to celebrate some, tolerate others and wipe out a third group of insects?

The work is sadly echoed by the result of recent studies that observed that insect populations have dramatically plummeted in Germany: the researchers counted that the country hosts 76 percent flying insects compared to 30 years ago.

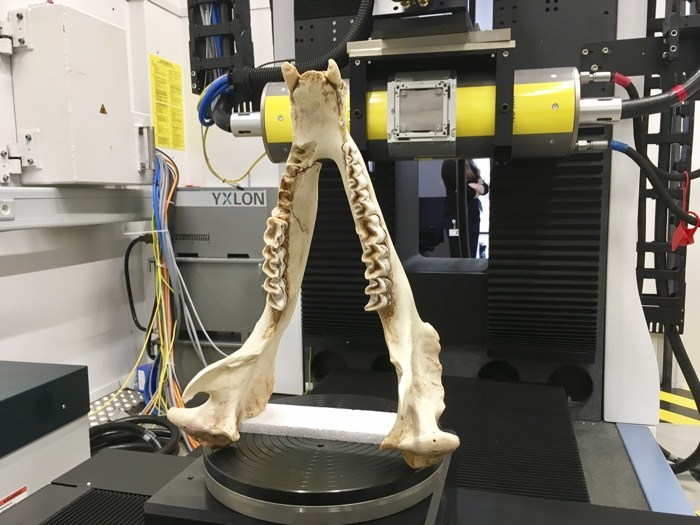

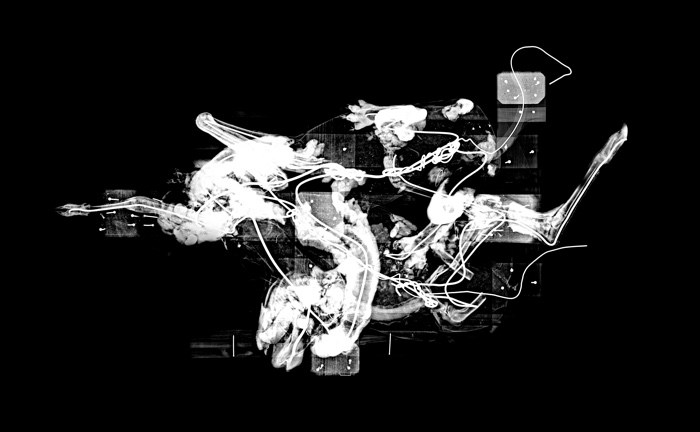

Lower jaw of the critically endangered Sumatran rhinoceros in the CT scanner of YXLON. Photo: Reassembling the Natural / Etienne Turpin, 2017

Skull of the critically endangered Sumatran rhinoceros in the CT scanner of YXLON. Photo: Reassembling the Natural / Etienne Turpin, 2017

As rhinoceros horns are in high demand on the black market, even the skulls of the already dead animals have been stolen from zoological museums. On the occasion of Disappearing Legacies: The World as Forest, CT-scanner developer Xylon International produced a high-res scan of a Sumatran rhinoceros skull from the Mammal Collection of the CeNak. Even the horn of the specimen was cut off before it was acquired for the collections.

Armin Linke and Giulia Bruno, Riau, (Sumatra) Indonesia. Photo: Reassembling the Natural/Anna-Sophie Springer, 2017

Drone Akademi Indonesia, Indonesian Province of Riau, Sumatra. Photo: Reassembling the Natural/Etienne Turpin, 2017

In 2014 activist geographer Radjawali Irendra founded Akademi Drone Indonesia (ADI), an organisation dedicated to research, education and policy surrounding unmanned vehicles for terrestrial and aquatic research and an advocacy interested in environmental issues.

Indigenous communities and poor people whose land rights are threatened use ADI’s drones to collect detailed spatial data, create their own aerial imagery and challenge official narratives.

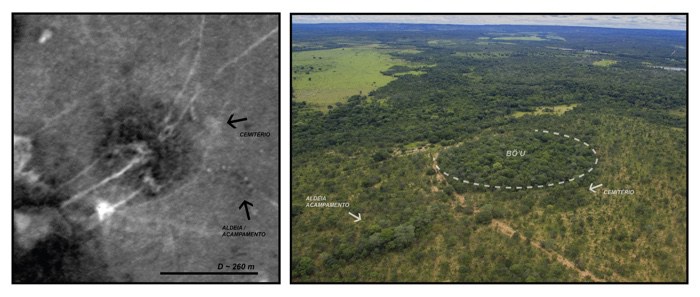

Paulo Tavares, Trees, Vines, Palms and Other Architectural Monuments, 2017. Satellite and ground identification of the ancient village of Bö’u, the old geopolitical center of the Xavante territory of Marãiwatsédé, which is still outside their demarcated land. Credit: Bö’u Association/autonoma

Paulo Tavares, Trees, Vines, Palms and Other Architectural Monuments, 2017. Policarpo Tserenhorã and Domingos Hö’awari conduct botanic inventory research in the cemetery site of the ancient settlement of Tsinõ. Credit: Bö’u Association/autonoma

From the early 1950s to the late 1960s, the A’uwe – Xavante people, an indigenous nation of Brazilian Amazon was subjected to a brutal land dispossession and forced removals to open space for giant cattle farms and soy plantation. The campaign was part of a strategy of territorial colonisation that the Brazilian military described as “occupying demographic voids.”

In 1966 the A’uwe of Marãiwatséde were deported from their ancestral land in an operation led by the Brazilian Air Force. In 1974, the State Indigenous Agency (FUNAI) emitted a certificate attesting that this territory wasn’t indigenous land anymore.

In collaboration with the Bö’u Xavante Association of Marãiwatséde, a team led by architect Paulo Tavares conducted a forensic analysis of the sites, mapping and surveying their ancient villages and cemeteries in order to provide evidence of their ancestral possession of this territory.

The sites studied display very similar feature in that a patch of vegetation had grown precisely in the arc-like shape of the ancient village. Made of a combination between medium and large trees, palms and other types of plants and vines, these botanic formations contain certain species that are associates with Xavante traditional occupation and land managing systems.

The botanic formations are the equivalent to an architectural ruin. Some of the questions raised by this research into forest wilderness/domestication include:

Can we claim trees, vines and palms to be historic monuments? Is the forest an “urban heritage” of indigenous designs?

Ursula Biemann and Paulo Tavares, Forest Law, 2014. Installation view

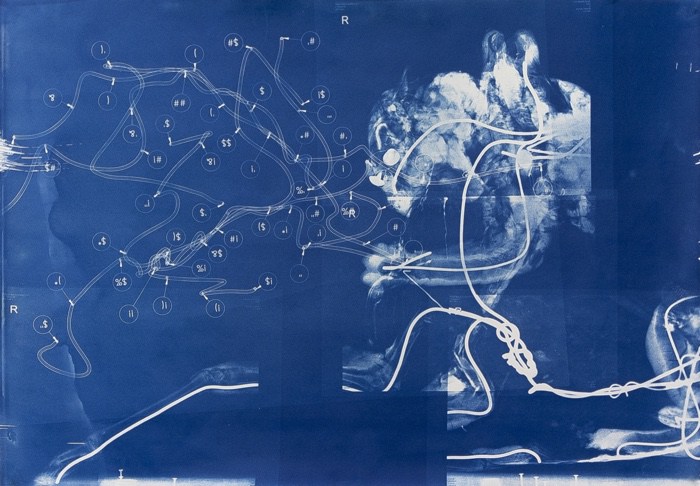

Revital Cohen and Tuur Van Balen, Paradise (multiply), 2017, cyanotype on paper. Photo: Michael Pfisterer

I’ll leave you with more images from the show and a text from Alfred Russel Wallace that reads like it has been written yesterday and not in 1910:

Yet during the past century, which has seen those great advances in the knowledge of Nature of which we are so proud, there has been no corresponding development of a love or reverence for her works; so that never before has there been such widespread ravage of the earth’s surface by destruction of native vegetation and with it of much animal life, and such wholesale defacement of the earth by mineral workings and by pouring into our streams and rivers the refuse of manufactories and of cities; and this has been done by all the greatest nations claiming the first place for civilisation and religion! And what is worse, the greater part of this waste and devastation has been and is being carried on, not for any good or worthy purpose, but in the interest of personal greed and avarice; so that in every case, while wealth has increased in the hands of the few, millions are still living without the bare necessaries for a healthy or a decent life, thousands dying yearly of actual starvation, and other thousands being slowly or suddenly destroyed by hideous diseases or accidents, directly caused in this cruel race for wealth, and in almost every case easily preventable. Yet they are not prevented, solely because to do so would somewhat diminish the profits of the capitalists and legislators who are directly responsible for this almost world-wide defacement and destruction, and virtual massacre of the ignorant and defenceless workers.

Alfred Russel Wallace, 1910

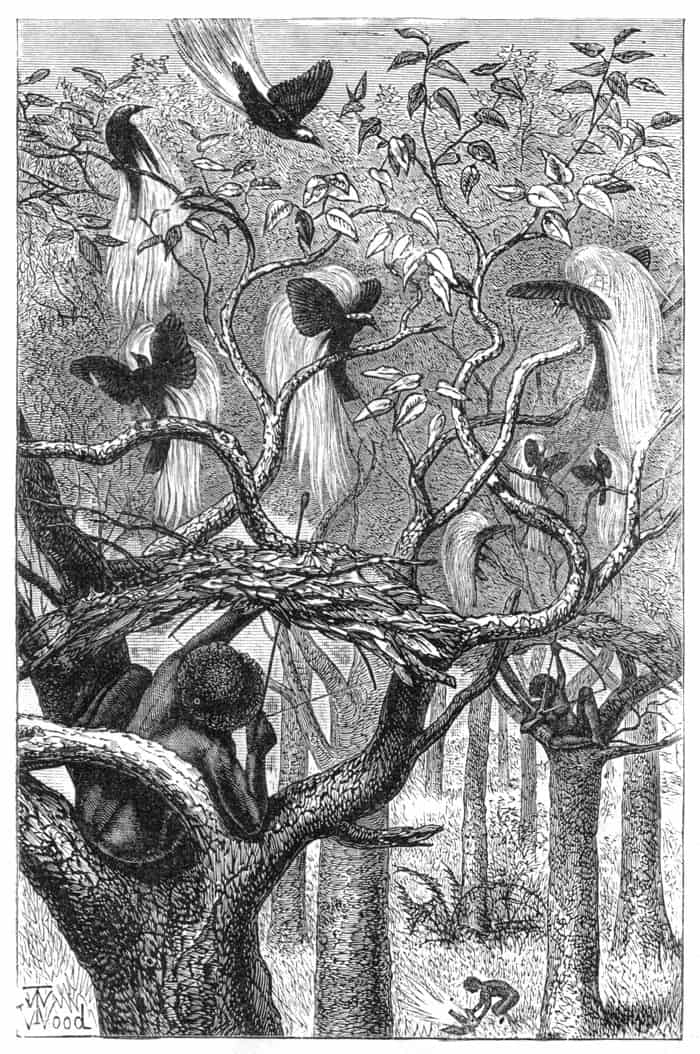

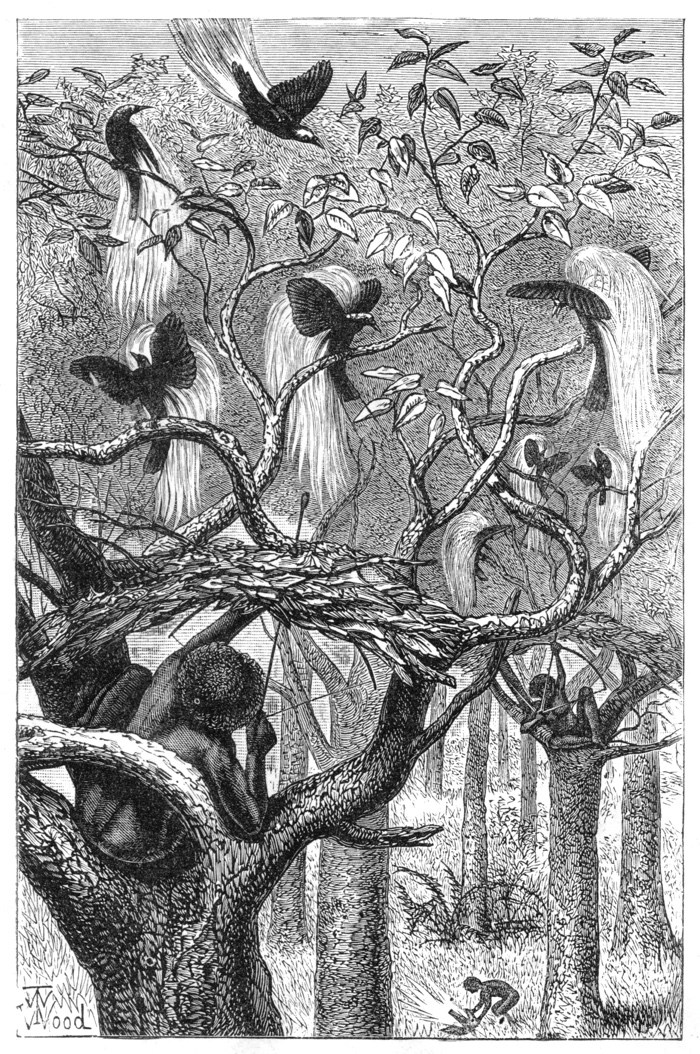

“Natives of Aru shooting the great bird of paradise”, in Wallace, The Malay Archipelago, 1869

Revital Cohen and Tuur Van Balen, Savane Du Sud Dessus, 2016

Revital Cohen & Tuur van Balen, Raggiana, Emperor, and Red (2017), neon sculptures made from rare neon, mammoth ivory, copper, and color. Photo: Michael Pfisterer

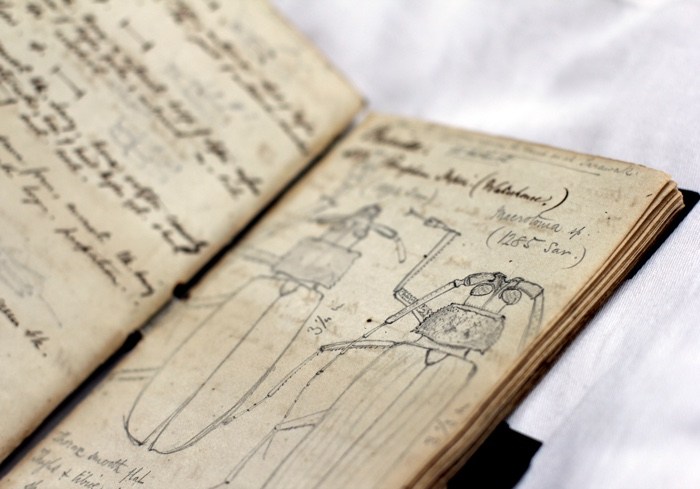

Beetle drawings in Alfred Russel Wallace’s Natural History Notebook, 1854. Photo: Reassembling the Natural/Etienne Turpin, 2014. Courtesy Linnean Society London

Palm oil plantation in the Indonesian province of Riau, Sumatra. Photo: Reassembling the Natural/Etienne Turpin, 2016.

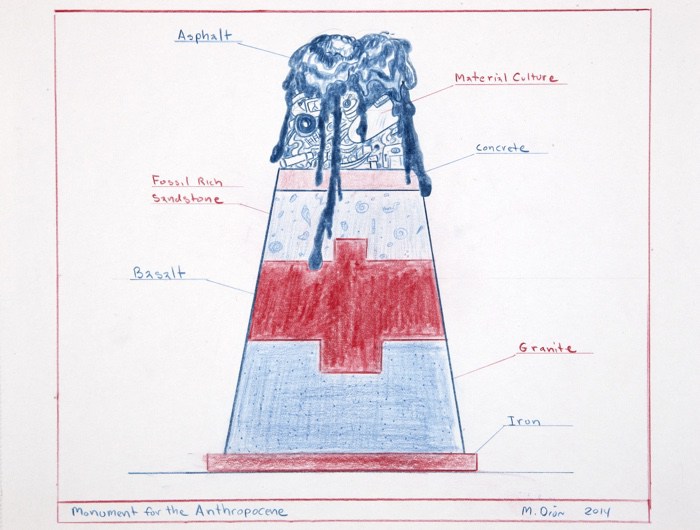

Mark Dion, Monument for the Anthropocene, 2014. Courtesy the artist and Galerie Nagel Draxler, Berlin/Köln

Exhibition view (Wallace panel / Mark Dion rhino replica.) Photo: ReassemblingNature.org, Michael Pfisterer

Exhibition view. Photo: ReassemblingNature.org, Michael Pfisterer

Exhibition view. Photo: ReassemblingNature.org, Michael Pfisterer

Verschwindende Vermächtnisse: Die Welt als Wald. Photo: UHH/CeNak, Reiss

Barbara Marcel, The Open Forest, 2017. Still from the Videoessay

Barbara Marcel, The Open Forest, 2017. Still from the video essay

Armin Linke, Palm oil plantation, Kecematan Bataian Kabupaten Rokan Hilir (Sumatra) Indonesia, 2017. Photo: © Armin Linke

Armin Linke, Fighting fire in the peatland, Kecematan Bataian Kabupaten Rokan Hilir (Sumatra) Indonesia, 2017. Photo: © Armin Linke

Armin Linke, Inagritech International Agricultural Machinery fair, truck for palm oil collection, Jakarta Indonesia, 2017. Photo: © Armin Linke

Previously: Palm oil, peatfires, Nutella and the anthropocene.

Disappearing Legacies: The World as Forest / Verschwindende Vermächtnisse: Die Welt als Wald remains open until 29 March 2018 at the Zoological Museum in Hamburg.

The exhibition is free.

Prof. Anna Tsing will give a keynote lecture on 26 March in the context of the Hamburg exhibition. On 26 April a second version of the exhibition will open at Tieranatomisches Theater in Berlin. In the fall, a third iteration of the exhibition will open in Halle/Saale.