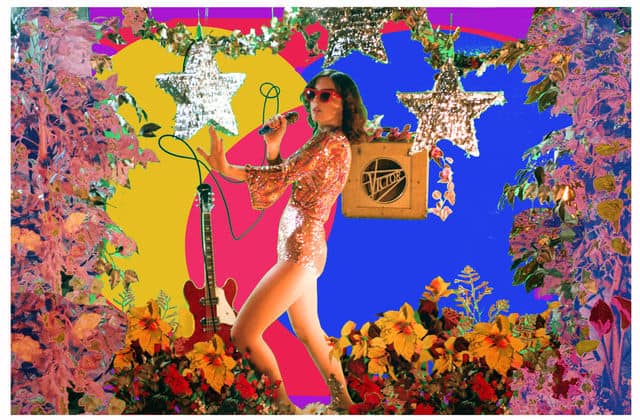

Nashville singer-songwriter Tristen has released her new music video, “Partyin’ Is Such Sweet Sorrow,” and her luminous libretto won’t be the only thing imprinted on your mind. While making the video, Tristen explored a question that has tormented many women: why our lives, characters, and overall beings are so often created by, for, and through the male perspective.

Tristen soaked in the man-makes-woman perspective, turned the tables by casting a “lover boy” to lip sync her satisfyingly melancholic vocals in the music video, and took back the power over her own womanhood. Tristen asks, “I am a woman writing, singing as a male character about his relationship with women. How often does that happen?” Her response is the ultimate woman-makes-man art form.

Tristen has not only flipped the script, but unlocked the door to even larger questions at hand: Where are all the women? Where are the complex and intriguing female characters? And where are the women’s lives and perspectives told by women? Tristen paired her music video with a powerful essay titled “Is Art Imitating Life or Just Limiting Women?”

Read Tristen’s essay below, watch “Partyin’ Is Such Sweet Sorrow” above, and prepare to be inspired to make your own magic.

Is Art Imitating Life or Just Limiting Women?

To me, great songs are stories set to music that reveal some hairy truth we can all relate to. I recently wrote a song about a barfly who lost his true love. My Henry Chinaski was coasting rock and roll’s rock bottom, with only the lonely enabling his addictive repetitions. “Partyin’ is Such Sweet Sorrow,” as I named it, needed a music video, and this archetype felt real after living in Nashville among artists, lost dreams, and fevered egos. For the video, I found a rugged, drunken lover boy with great hair to lip sync my song, while the voice was still mine. I’m thinking, I am a woman writing, singing as a male character about his relationship with women. How often does that happen?

I’m talking to a friend on the phone, feeling like a unicorn in hell’s dick forest, and I remember that I must focus my feminine powers on wedging myself into my favorite spot: Promoting the confusion, creating questions, flowing with fluidity, and hanging in the mystery space of differentiation, identification, categorization, and cultivation of self. I remember how fitting in always feels hard for those with a sensitivity to contradiction.

My friend asks, “Who are your favorite female characters written by women?” I pause, thinking. Harper Lee, The Handmaid’s Tale, Meryl Streep in Heartburn, Celie in The Color Purple, “Amelia” by Joni Mitchell, “Jolene” by Dolly. I’m stalled. This is hard, so I break it down. What are my favorite works of fiction written by women? I think of a few more, but I’m mostly grasping at straws. I tell my friend that I’ll have to call him back. Why was this so hard?

So, I consult further data. According to the study Gender and the Billboard Top 40 Charts between 1997 and 2007, women make up only about 11% percent of the total number of songwriters, yet 37% of the songs had women contributing to lyrics. The Center for the Study of Women in Television and Film’s recent study had women accounting for 13% of writers. Salon reports that women in literature are doing better, making up about 30% of most publishers’ rosters, and about the same percentage, 33% percent, are getting reviewed in publications. And we’ve all heard the classic tales of women writers using a nom de plume to seem like dude.

Even if I accept the numerical disadvantage of finding female writers, I still must dig for female characters because, according to Gender Bias Without Borders: An Investigation of Female Characters in Popular Films Across 11 Countries, as of 2014, named females only account for 1 out of 3 characters, and only about 23% of films have a female protagonist or co-protagonist at all. Got it. There are fewer female characters being created, but hey, not all boys are bad at writing interesting female characters, right?

The walls draw in closer as I read about the Bechdel Test. A little more than half of movies currently pass this test, which requires a movie to have at least two women in it, who talk to each other, about something besides a man. Virginia Woolf wrote in A Room Of One’s Own in 1929, “It was strange to think that all the great women of fiction were, until Jane Austen’s day, not only seen by the other sex, but seen only in relation to the other sex. And how small a part of a woman’s life is that.” Men have created the few images of women that exist, and about half of those characters aren’t written realistically. Woolf notices, “All these relationships between women, I thought, rapidly recalling the splendid gallery of fictitious women, are too simple.” Is this why my female relationships are constantly plagued with talk of men and love? Are we only mimicking mens’ image of us?

Humans learn to communicate through mimicry. After our parents replicate themselves into us, they impress their unlived dreams onto us. My mother, pregnant and then married at 18, would tell me, “Don’t get married until you’re 30.” Too often living in Nashville, we see musicians grooming their three-year-olds for a life on the stage. A teenager delineates Bob Dylan’s career before he’s ever worked a job or fallen in love. We grow and learn inside the reflection of our parents’ regrets, misfortunes, or expectations for greatness, that even they could not achieve.

We mimic what we see. When my one-year-old niece tried to make her my sister laugh for the first time, she strutted around the room talking into the palm of her hand, babbling and laughing. This toddler looked as if she was talking to a little person in her hand. We finally realized she was imitating my sister talking into her phone while on FaceTime. And this little girl is growing up in a habitat of images, instant information, communication, and connectivity. The black mirror now permeates our development.

And it’s so new. Only within the last 100 years, humans have establish widespread radio communication, the television, and finally, in the last 30 years or so, the internet, which for the first time allows instant communication between the users of the technology. According to the Nielsen report, each day, Americans are immersed in their screens for about 5 hours of television, an hour on the internet, and three hours of radio. These screens most likely show images of women created in the tradition of men’s fiction. In all of this, sadly, the rare, oversimplified depictions of women, usually in relationship to men, are hypnotic mirrors for men, too.

And as a great leveler and oppositional reaction, I can swear off male artists forever, but this feels like the tool of the oppressor, just further dividing and reacting, and it feels too simple. How can I become the change I want to see while men’s art is within me still? It flows in the conversation of consciousness, my mimicry, and therefore, my creations. The only solution I can see is to reveal the concealed conversations through my work.

It’s called the conquest for truth, because truth is not a trust fund that kicks in when you are eighteen. It is not a gift; it must be discovered. You must perpetually pull weeds from the garden, so flowers can grow. You must accept that when you are sleeping, there is always someone willing to distort, obscure, obfuscate the truth, in hopes of getting a leg up. Regardless of gendering the writer and gendering the characters to establish the numerical meekness of the female writer’s scream, men and love of men are still the usual subject of mainstream women’s art. Just one more truth to survive and thrive in, because right now, as you are reading this, despite all of this, it is still the best time to be a woman. Woof. Or maybe Woolf.

So please don’t bore us, get to a female singing a chorus, where the lyrics are about something other than a man. It’s clear that women see very little representations of their own complexity from their own perspective in art. So before you are eaten by time, catch the wave of reform with your surfboard, and even more so, revere or unearth the untold stories in art. As we distill the human experience into a clever turn of phrase, and as these characters mesmerize the masses, I’m only asking that art imitate life, rather than limit women.

Top photo courtesy Tristen

More from BUST

Dream Nails Fights For Reproductive Rights With Their New Single “Vagina Police”: BUST Premiere

Poet Olivia Gatwood Writes Like Teen Spirit: BUST Interview

Amanda Palmer’s Tribute To The Cranberries’ Dolores O’Riordan Will Make You “Cry Goodbye”