In Esperanto, the word “vero” means “truth.” In English, vero doesn’t mean anything ― it’s just the name of a photo-sharing Instagram competitor. Until recently, both versions suffered from the same fundamental problem: Nobody was using them.

The pool of people using Esperanto still remains fairly small, but this week the Vero platform exploded in popularity, becoming the top ranked social media app on both the App Store and Google Play.

Vero’s sudden success seems to have taken even the company by surprise, with the swell of signups overwhelming its servers and temporarily slowing them to a crawl Monday and Tuesday.

Vero strongly resembles the Facebook-owned Instagram in both form and function, but it sets itself apart in three key ways:

First, Vero is an advertising-free platform, which, unlike Facebook, means it won’t be collecting and selling users’ data to the highest bidder.

Second, unlike Facebook, Vero doesn’t use a sorting algorithm to prioritize (and monetize) content in your feed, a source of much anger on Instagram.

Third, since it’s ad-free, Vero aims to support itself via a subscription model. The details here are a little sparse, with the company saying it will charge “a small annual fee” of a couple bucks a year. The company is offering free lifetime service to its first 1 million users.

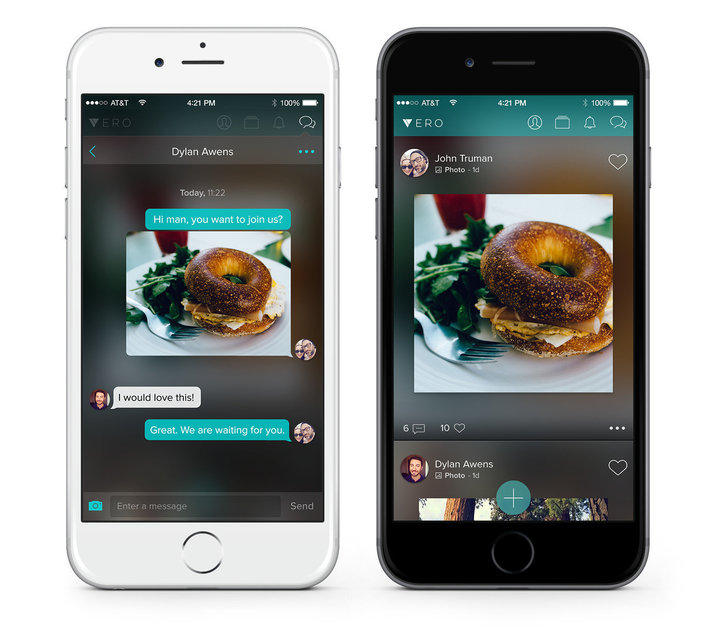

Here’s what the app itself looks like:

The app, backed by the billionaire Lebanese businessman Ayman Hariri, has been around since 2015. It’s unclear what prompted the renewed interest this week.

“When I did [join existing social networks], I found the options for privacy were quite limited and difficult to understand, and also when I decided to get on and connect with a few of my friends, I noticed that their behavior online was very different than their behavior in the real world,” Hariri told CNBC at the time.

“We felt that by excluding ads out of our business model … it allows us to look at our users as our customers, rather than advertisers,” he added.

Vero’s success now hinges on its ability to convert this week’s signup spike into a solid base of daily active users. If it fails, it risks being relegated to the same category as Ello, a Facebook competitor that also pledged to rid itself of advertisers back in 2014. It grew rapidly for a short time before ultimately fizzling out.